THE

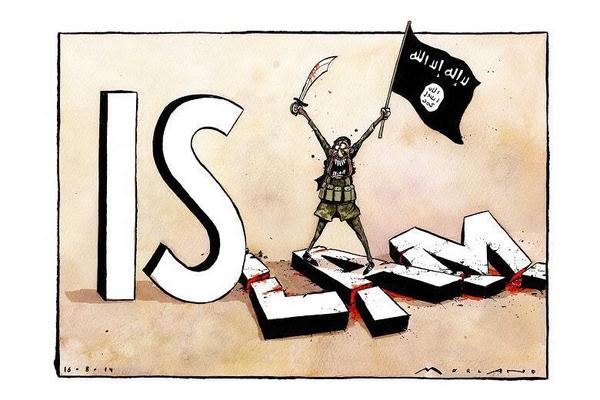

notion that the Islamic State (ISIS), or Da’ish, would not extend its reach to

South Africa has proved a false one. ISIS, which controls swathes of Iraq and

Syria, has persuaded thousands of gullible youths from all over the Muslim

world to migrate to its self-declared Caliphate.

This

breakaway group from Al-Qa’idah has turned Islamic extremism on its head.

Unlike Al-Qa’idah, which has focused on a “distant enemy” from caves and

compounds, ISIS controls actual territory and has an active militia.

And whilst

Sunni scholars world-wide have condemned ISIS for its heartless parody of

Shari’ah, or Sacred Law, and its notion of an “Islamic State”, it has not

prevented it from becoming an ideological reality bolstered by extensive social

media support.

Its

online magazine, Dabiq, presents a glowing depiction of jihadist utopia. But

the gloss disappears when the Caliph urges Muslims to rise up and kill

“crusaders” (Christians and Jews).

Essentially,

ISIS’ message is that Islam is under threat everywhere; the world is a Dar ul-Harb, a place of hostility, and

ISIS offers the only Dar us-Salam, or

refuge. “If you don’t agree with us, you’re against us” is the gist of the

worldview, which means that as a Muslim if you disagree with ISIS you become a kafir – an unbeliever whose blood, in

their eyes, it is permissible to spill.

ISIS

also promotes an apocalyptic vision of Syria, and claims that it is waiting for

the end days and the final Islamic Armageddon when a leader, the Imam Mahdi,

will appear.

ISIS

rose after 2003 – and the US invasion of Iraq – as an Al-Qa’idah affiliate led

by Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi. He was a Jordanian jihadist with a criminal record,

who refused to swear allegiance to Usama Bin Laden, and whose brutality even

stunned Al-Qa’idah.

The

rot was started by the Bush administration when Paul Bremer, the US

presidential aide in Iraq, fired 250, 000 civil servants and government forces.

Bush’s incompetence in then imprisoning many Iraqi officials created a

political sinkhole into which the whole region collapsed as Iraq disintegrated.

Interestingly,

General David Petraeus – who was sent to Iraq in 2007 as “Mr Fixit” – told the

Assad regime that its sponsorship of a Salafi insurgency to undermine the US

would come back to haunt it. Nouri al-Maliki’s government (2006-14) caused

further resentment when he condoned Shi’ah sectarian patronage and allowed political

neglect of the Sunnis.

It is

more than anecdotal, reports the German magazine Der Spiegel, that the

structure of ISIS was developed by a bitter, unemployed ex-Baathist

intelligence officer, Colonel Samir al-Khlifawi. Like so many Iraqis, he’d been quietly

waiting to seize the day.

However,

post-analysis does not serve present realities in South Africa. This is because

although ISIS does have a decidedly limited appeal here, a few South Africans

have been seduced by its propaganda and have travelled to Syria either to fight

with it, or to migrate permanently.

In

recent months, swirling speculation and rumour has coalesced into fact. In

South Africa, ISIS is calling.

The

first instance was earlier this year when the Daily Maverick interviewed via

social media an “Abu Hurayra” from Gauteng, who claimed to be fighting with

ISIS, saying that another South African “Abu Baraa” was with him.

Last

month a teenage girl from Kenwyn was apprehended at Cape Town International

airport whilst en-route to Syria. Hailing from a middle-class home, it emerged

that she had been active vis-a-vis ISIS in social media. Someone who knew the

family described her as intelligent, focused and difficult to dissuade.

With

the family closing ranks, it has been a tough lead to follow. In addition, state

security has either been unable – or unwilling – to explain to the media who

gave the girl, a minor, guardian’s consent to board the plane. It is a missing

link in the narrative. The question is: who was her handler?

A

Spanish journalist following the story, Jaime Velazquez, believes that part of

the answer might lie at school, but that doors have closed there too on the

possibility of an educator playing a role.

In May

the Roshnee community near Johannesburg was rocked by the revelation that more

than 20 of its members had left for Syria. Eleven were arrested by the Turkish

authorities and deported, but the rest reportedly got through.

A

meeting expressing public concern was attended by over a thousand people at a Roshnee

mosque and was addressed by local scholars, who explained to the congregants

the theological pitfalls of the Caliphate.

Shortly

afterwards, the Lenasia-based radio station Channel Islam International (Cii)

received a letter, allegedly penned by South Africans with ISIS, criticising

the scholars and telling them “to see for themselves” and not to believe the

western media.

Close

on the heels of the first letter, Cii published on its website an e-mail from a

Rashid Moosagie, believed to have been from Port Elizabeth, and a member of

another group that had reportedly migrated to Syria and the “promised land”.

In a

rambling diatribe against what he perceived as reprehensible, polytheistic

Indo-Pak Islamic culturalism, the author claimed that South African Muslims were

apologetic capitulators, and that most local groups – including the spiritually

inclined Sufis and the “Tablighis” who propagate faith to fellow Muslims – were

practising unbelief.

At the

time of writing, various role players in the community were scrambling to

formulate a united and coherent response to South Africans being recruited by

ISIS, one of the most brutal, the most unforgiving and the most distressing

versions of extremism to ever hit our shores.